Leadership has many different facets but essentially a leader influences people to accomplish a common goal (Camp, 2010). Self-differentiation is key to effectively leading change because “a differentiated leader can take a well-defined stand, even when followers disagree, while remaining connected in a meaningful way with others (Camp, 2010).” There are always going to be strong emotions involved during a change. Change is stressful in a visceral way on the body (Wisse & Sleebos, 2015). If we can learn strategies that allow for self-differentiated leadership, then we will be able to diffuse the anxiety of the people in the organization.

Education tends to be an emotionally charged environment. I believe this is due, in part, to the fact that educators are passionate about their work. They care deeply that their work teaches and inspires each student to reach their potential. Therefore, changes are closely scrutinized and sometimes resisted. A self-differentiated leader can respond to an anxious organization with a non-anxious response and diffuse any triangulations that have formed. When implementing a change strategy, like my innovation plan, leaders must be prepared to deal with sabotage. Though not always intentional, sabotage of a differentiated leader’s initiatives often indicate that the leader is doing the right thing (Camp, 2010).

As we discuss change, organizational anxiety, and sabotage, I want to run and hide! I believe that I possess many wonderful leadership qualities. However, my ability to cope with confrontation is not one of my strong suits. In fact, my organization recently had each employee complete an Emergenetics profile and workshop. The Emergenetics profile connects a person’s behavior with their thinking style to aid in self-understanding and interacting well with others in the organization. My profile indicated that my behavior falls in the lowest range of assertiveness. Learning more about how to handle the crucial conversations that are a necessary part of leading organizational change is especially helpful for me.

A conversation becomes crucial when there are differing opinions, high stakes and strong emotions. It is very easy to move to silence or violence when faced with these conversations (Patterson et al., 2012). My go-to reaction is generally to move to silence and avoid or remove myself from the conversation. However, when people move to silence or violence it takes us out of dialogue and we lose the opportunity to move toward our goals. The crucial conversations methodology outlined in the video above and in the book Crucial Conversations (Patterson et al.. 2012) is going to be an instrumental part of implementing my innovation plan and change strategies.

1. Start with the Heart

We are biologically wired to perform badly when we experience strong emotions. It is very easy to lose sight of our main goal in the conversation. Starting with the heart reminds me to focus on what I really want. I don’t simply want to “win.” I really want to understand, maintain the relationship and move toward a common goal. Taking a mental step back to clarify my motives will allow me to avoid making a “fool’s choice.” Rather than believing there are only two options, I will frame my questions and strive to come to solutions that involve the word “and.”

2. Learn to Look

Learning to look means tuning into the verbal and non-verbal cues that indicate the dialogue is breaking down. I will pay attention to body language (stillness, crossed arms, facial expressions, etc.) and verbal cues (sarcasm, personal attacks, etc.) throughout the conversation to monitor when I may need to employ strategies to reinstate safety and get the dialogue back on track.

3. Make it Safe

When I notice that dialogue is breaking down, it is usually because someone feels unsafe. Safety is paramount for individuals to remain in dialogue. When safety is compromised it is important to take steps to restore safety for everyone. That may look like apologizing and clarifying what I did or did not mean. Safety can also be restored by finding and maintaining a common purpose. I want to make it safe for all parties to contribute their thoughts, ideas, opinions, concerns, and solutions to the ‘pool of meaning’ (Patterson et al., 2012).

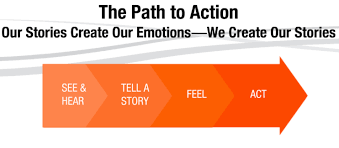

4. Master my Stories

It is important to manage emotions during crucial conversations. Our emotions usually stem from the stories that we tell ourselves or the meaning we make from what we see and hear. Stories are not facts, but they often generate an emotional response which then affects our actions. This is known as our “path to action.” I will be more mindful of the stories that I tell myself and question whether I am drawing valid conclusions. I will strive to use fact rather than story to drive my actions.

5. State my Path

S – Share your facts

T – Tell your story

A – Ask for the other’s path

T – Talk tentatively

E – Encourage testing

In order to present a persuasive argument I will start with the facts. Facts are more credible and persuasive than subjective stories. I will encourage others to contribute to the dialogue and let them know that I welcome their honest thoughts and opinions. I will be careful to avoid becoming defensive if others question or dismiss my story or disagree with me. If there are signs that anyone is turning to silence or violence I will respond with restoring safety. To avoid breakdown of the dialogue I will talk tentatively rather than abrasively.

6. Explore Others’ Paths

In this step, I will strive to stay in curiosity rather than judgement. If I am genuinely curious to hear the other person’s input it will be much easier to manage emotions and find common ground. Sometimes people are hesitant to honestly share their path, especially when it may be unflattering or contradictory. I will use the “power listening tools” of asking, mirroring, paraphrasing and priming to help encourage open dialogue (Patterson et al., 2012).

7. Move to Action

It is important to end a conversation strong. Determining actionable next steps that take into account the entire ‘pool of meaning’ will help to keep all parties on the same page knowing that everyone’s voice was heard and genuinely considered.

Conclusion

I will strive to improve my communication skills to become a leader who can handle crucial moments and conversations successfully. I am confident that self-differentiation combined with an effective crucial conversation strategy will propel my organization toward our goals.

References

Camp, J. (2010, November 10). Friedman’s Theory of Differentiated Leadership Made Simple. Www.youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RgdcljNV-Ew

Crucial conversations 7 principles. (2023). ReadinGraphics. Retrieved April 29, 2023, from https://readingraphics.com/book-summary-crucial-conversations/.

Patterson, K., Grenny, J., Mcmillan, R., & Switzler, A. (2012). Crucial conversations: tools for talking when stakes are high. Mcgraw-Hill Education.

Wisse, B., & Sleebos, E. (2015). When change causes stress: Effects of self-construal and change consequences. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31(2), 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-015-9411-z

One response to “Leadership & Crucial Conversations”

[…] LEADERSHIP & CRUCIAL CONVERSATIONS […]

LikeLike